A Larger Framework

Summer Shows, philanthropy, the future of art in Billings, the totality of it all, beauty

Oh, hello. That took a little longer than I expected. Whatever the case, it’s another Toucan Newsletter, sporadic, it turns out, but longer, when it does transmit. As always the information that includes pertinent dates and times is at the top. As for the rest, read it, skim it, skip it, however you want to engage with it, just know that it’s produced for you, a subset of souls that I invoke again at the end (how’s that for a tease?).

Also, these emails are often too long to fully render in most email applications, so just click on the link at the bottom when you get there to continue, or you can click on the title above right now to go directly to this post on the Substack site (probably a better reading experience, anyway). (If you’re already in the app, disregard all of that.) Onward.

THE TOUCAN SUMMER SHOWS

First, a series of artist features we’re doing this summer. The Toucan Summer Shows, we’re calling it, this particular cluster in time and space of artists and their work. We will open these shows on Saturdays, with a reception from 1 – 3 pm.

June 7 – July 3 | Betsy Thayer

We will be featuring the artwork of Billings artist, Betsy Thayer. Utilizing a vast array of media and life experience, she has found, in her words, “moderate success based on dumb luck and nepotism,” and has thus “justified maxing out my credit cards buying art supplies.”

July 12 – August 12 | Monica Bergquist

We will be featuring the artwork of Helena artist, Monica Bergquist. Painting again after a 20-year hiatus, when she recognized the need to refocus on her passion for creating art after her mom passed away, Monica’s fluid abstraction is expertly crafted and compellingly complex.

August 16 – September 20 | Ty Kelly

We will be featuring the artwork of Big Timber artist, Ty Kelly. A zig-zag life after the completion of an education in architecture has led Ty back to Montana to build custom homes and focus on his deep and enduring passion for making visual art.

More information on these shows will be available as they draw nearer.

The photographer and essayist Robert Adams, taking inspiration from the American poet and novelist James Dickey, wrote that objects and actions of consequence “can only be found in a framework that is larger than we are, an encompassing totality invulnerable to our worst behavior and most corrosive anxieties.” That totality—while perceptually obscured for many of us mortals in our current moment of socioeconomic and political instability, with the human condition somehow, and almost incomprehensibly, under attack—that totality is what shines the light of revelation on the murk of obfuscation brought by too narrow of a view.

This is a photograph of Mexican architect Frida Escobedo. She is rising rapidly into the upper atmosphere of artful building. A major commission in the United States is a rocket to her renown: the new wing for Modern and contemporary art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The design, from what I’ve seen in the architectural press, is a bold statement of light-filled volumes, appropriately personal (with hints of the heritage and vernacular of her homeland) yet public in its form and function, meaningful and monumental in a city filled with architectural monuments dedicated to the arts.

This new addition will be known as the Oscar L. Tang and H.M. Agnes Hsu-Tang Wing for Modern and Contemporary Art, named for the couple who tipped the long-gestating project into reality with a $125 million dollar gift. A recent profile in the New York Times was headlined, “The Tangs, New Donor Royalty, Step Into the Spotlight.” Long a low-profile player in the cultural infrastructure of New York City, the convergence of several high-profile products of their philanthropy has focused a spotlight on their generosity. In addition to the Met, there is the Oscar L. Tang and H. M. Agnes Hsu-Tang Music and Artistic Director of the New York Philharmonic, and the Tang Wing for American Democracy at the New York Historical Society. Among much more.

It takes people like the Tangs to make and sustain the underpinnings of culture in this country, especially now, when our public investment in such things is at so much risk. That the Tangs private success would transfer to the public good via philanthropy directed toward this country’s most significant institutions of art and culture is testament to their benevolent vision and resolve directed toward the greater well-being of our shared humanity.

And while philanthropy is sometimes perpetrated in a reductive way, simply for renown, if not vanity, the Tangs—educated, erudite, and experienced (Agnes is a working scholar with a PhD. in art and archeology, after all, among other things)—their interest in the arts could never be described as anything so base, or merely as a product of wealth.

The relationship of art and philanthropy is known and necessary, of course, in as much as the arts don’t readily exist within our contemporary capitalistic economy with the same vitality as more mainstream tastes and vices and fundamental needs facilitate. This reality is pronounced in a place like Billings, which by its very nature, its ideological underpinnings, is so reluctant to embrace the unconventional, the unprecedented, the unknown.

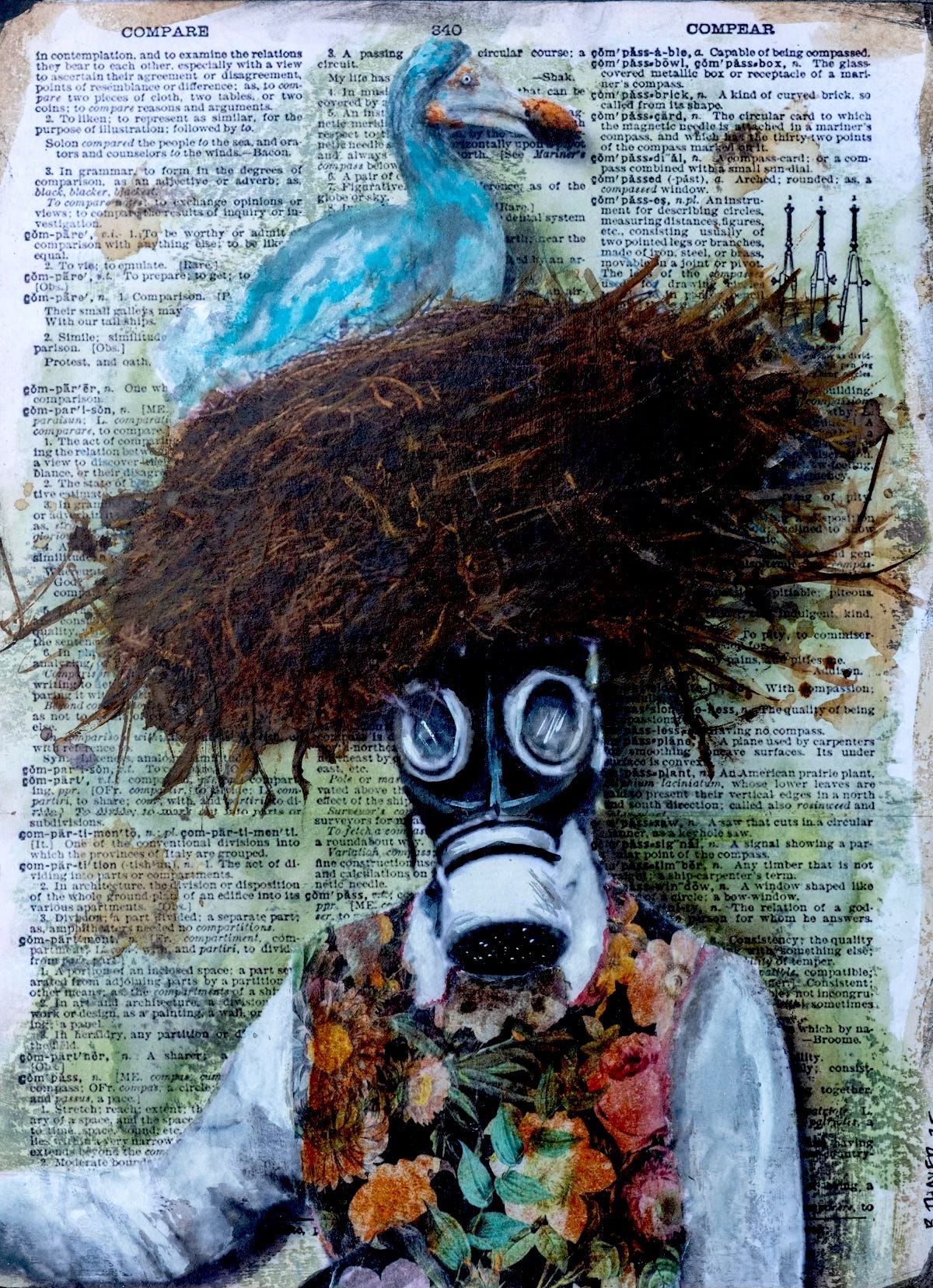

Because look, Allison and I have been working as creative people in Billings for a very long time. The images of Allison’s artwork in the clipping, above, from the Yellowstone Art Museum Auction catalog from 1999 attest to as much. And the clipping of a contact sheet, below, from a public service campaign I shot (doing business as Imagimark! Productions, which I’m back to doing) for Tumbleweed, also in the late 1990s, should do the same. Which is only to say that we’ve done a lot of things and seen a lot happen here, seen things come and go, and, maybe most of all, we’ve seen a lot of things simply not happen.

When we bought Toucan, going on 19 years ago, born of ambition, yes, but more of opportunity (we consider ourselves accidental shopkeepers, to be honest), we decided to pursue a mission explicitly not to conserve the past, the legacy of art in Billings, but rather to try to contribute to building a future for art in Billings, to do what we could to make progress in the state of the art of the realm, while still dancing with the body politic and the specifics of the marketplace in order to be in business at all. This spirit, our reason for being, if you will, also informs our own philanthropy.

And so it was that a little more than a year ago, Allison and I, in the name of Toucan, established a program, in collaboration with the Art Department at Montana State University Billings and the MSU Billings Foundation, to reward senior art students with a financial incentive to make art and be artists in our community. The Toucan Capstone Award is a $500 grant given to a senior art student to aid in the funding of their Capstone Exhibition, the culmination of their undergraduate artmaking practice. And the Toucan Emerging Artist Award is a $500 grant given to a senior art student upon graduation as a token of seed money to support their artmaking in the real world, their practice immediately outside the confines of the academy, left to fend for themselves as artists in the wild.

The process of choosing the winners of these awards is a process that neither Allison nor I take lightly. There is an application that we developed to organize the process in an objective way, while realizing that the nature of art and the artists who create it exists entirely in the realm of the subjective. We engage the Art Department at MSUB in the process, Jodi Lightner, the department chair, in particular, for additional perspective and insight. And then from this alchemy of inputs, that in the end can barely be described in conventional terms (again, this is art we’re talking about) a deserving recipient emerges.

The first to receive the Toucan Emerging Artist Award, a year ago now, at the end of the semester last spring, was Emmit Bartsch. Emmit’s story of becoming an artist is convoluted in the productive way that many artists find their way to do what they do, be who they are. For Emmit, two unlikely vocational companions had set themselves against each other. In Emmit’s words, “It was either like, I’m going to be an artist, or I’m going to play sports professionally. That was, like, the only two things.” Sports diminished (not without some offers to play at the college level), and then came the kind of path unknowable until after the journey is done: a start at the University of Montana led to an epic road trip that coursed through Seattle, stopping to sell screen-printed t-shirts at the Fremont Market before heading down the coast to California and then back to Montana, dropping out, starting up again, dropping out, until eventually graduating from MSU Billings with an art degree.

Emmit’s application to our awards program expressed a kind of motivation and entrepreneurship that aligned with our own, a particular quality, among others, that propelled him to the summit of consideration for our inaugural Emerging Artist Award.

The recipient of the very first Toucan Capstone Award, given this past fall to aid in funding her final academic exhibition, hung at the Northcutt Steele Gallery on the MSUB campus this spring, was Carley Haskell. And while her path was a little more direct than Emmit’s, it still had that searching quality that animates most any artist’s practice of expression. Born into a Mormon family that split from the church when she was four, she still grew up in the shadow of that culture, in her words, “traditions, rituals, homemaking, not in an oppressive sense, but in the things we do to beautify things” in that environment, a grandmother’s china, glass, tablecloth. “I just found that really beautiful.” An identity as an artist developed early, and as she says, “I knew I wanted to teach art when I was in eighth grade.” A start at MSU in Bozeman was stymied, eventually, by this simple fact: “I just couldn’t find an apartment.” And so, finding a place for her passion at MSU Billings became not just a fallback position, but a meaningful, nurturing necessity. And while not in any way a given in the design and facilitation of this Toucan awards program, Carley, in fact, was also the recipient of the 2024-25 Toucan Emerging Artist Award, announced just last week.

As of today, Emmit has opened an art space in downtown Billings and Carley has accepted a job to teach art at Laurel High School. This is exactly what we had hoped for this program, that it could somehow play whatever small part in building a future for art in Billings, this progressive philanthropy directed toward improving the conditions for being human in our hometown.

The Greek root of “philanthropy” can be translated, literally, as “loving people.” Today, the word is more often associated with money, specifically that given for humanitarian purposes of some kind. The mechanism for this, legally, economically, is animated by currency and tax exemption, but where true businesspeople might obsess over such economic machinations, we most often treat Toucan as less of the capitalistic enterprise that it necessarily is and more as simply a labor of love.

And while our version of philanthropy cannot be compared in any way at the same financial scale, Oscar Tang alluded to something similar not that long ago in Billings. The Tangs’ own human spirit, it turns out, infiltrates not only the many cultural institutions they support, but a private company that Oscar Tang purchased in 1981 called Kampgrounds of America. When Oscar spoke last summer at the opening of KOA’s new international headquarters building in Billings, he commented on the fact that as a “Wall Street guy” the expected course would have been to flip this particular investment made after the 1970s energy crisis had tanked KOA’s stock price, reap the subsequent financial reward, and move on. However, in his words, he “fell in love” with this company dedicated to a network of campgrounds located across the United States and Canada, now more than 500 locations, this infrastructure built to support the kind of adventure, memories, and family connections that camping uniquely provides, and thus he and Agnes remain its sole owners to this day.

And so it is, with the world on fire and when Billings is just a little too much Billings (“We’re a city that doesn’t need all the bells and whistles.” – Bill Kennedy, City Council, Ward 3), we persevere with a dedication to sustain and forward a place of and for nothing less than the big idea of beauty, and to love the people who would value such a thing.

Insight from a couple of German philosophers might be apropos at this time, in this time: Friedrich Nietzsche believed that beauty, especially in art, has the power to transform suffering into something meaningful. He argued that art reconciles us to the tragic nature of existence by presenting it in a form that we can affirm and appreciate. On the other hand, Arthur Schopenhauer thought that the aesthetic experience provides a rare respite from the inherent suffering of life as facilitated by the ceaseless striving of the will, that it creates a kind of temporary, peaceful oblivion. For Nietzsche beauty creates meaning, for Schopenhauer, temporary relief.

Whatever your own inclination (I know what mine is), I think that maybe in order to live in a place like Billings, we’ve had to make a place that isn’t quite of Billings, for ourselves, of course, but also for the people who seek the same, for that is ultimately the community that Toucan generates. A subset of souls that find in Toucan a link, a connector, a portal, perhaps, to a circumstance, an ideology, a beauty, greater than the reality of this place.

When Agnes Hsu-Tang visits us at Toucan so that we may assist her in framing, preserving and presenting, the artwork she places at KOA’s headquarters, it is one more reminder that Toucan has continually afforded us, well, a link, a connector, even if only via threads gossamer thin, to objects and actions of consequence that, in Robert Adams’s words, once more: “can only be found in a framework that is larger than we are….” And that, perhaps, is the most beautiful thing of all.