Patience is a virtue, we hear. But, "Lingerer, my brain is on fire with impatience; and you tarry so long!" wrote Charlotte Brontë in Jane Eyre. If patience is indeed a virtue, then construction must be its curse. Everyone we encounter has the same story, but in the process of constructing a new Toucan in a new place, I fear we may have entered the Heart of Darkness with respect to the delays, or as Joseph Conrad wrote: "I might just as well have ordered a tree not to sway in the wind." The literary can be a comfort, the easing of our angst with the artful organization of the language that describes our predicament, but when your livelihood is at stake, words are never enough.

The new Toucan is coming, however, and we've enlisted deep breathing, chamomile tea, mind-clearing meditation, and long swims at the Y, to counter the angst wrought by the inevitable delays. It's a bit disorienting, to say the least, to be out of our Montana Avenue location and yet be unable to occupy our new place at 1002 2nd Avenue North. Toucan—the art gallery, gift boutique, and custom picture framing shop that it is—exists right now in Allison's and my dining room, two storage units, and the climate-controlled, enigmatic otherworld of my childhood bedroom at my parent's house.

The great American essayist, E.B. White, wrote: "And in every place he abandons he leaves something vital, it seems to me, and starts his new life somewhat less encrusted, like a lobster that has shed its skin and is for a time soft and vulnerable."

Toucan has existed for 17 years in Allison's and my hands, and it was around for 25 years before that. Now, it exists nowhere but in dissociated temporary outposts and the resultant vulnerability of not having a place to be. To pass the time, I think of the steel pieces on the ground around our new building as bones, skeletal remains unearthed from the tundra, waiting to be resurrected into a living architecture that will shelter the artifacts and processes of our existence in this place we call home.

We recently had a sneak peek of the Art House Cinema & Pub expansion—every bit as delayed as our project—and commiserated with Executive Director, Matt Blakeslee, about the nature of progress, i.e., it isn't easy. They got there, though, at Art House, and we take that as some solace that we will get there too. We're pleased to continue to support Art House and their contribution to the culture of our community and look forward to being able to join them in that effort again soon.

We’ll have a parking lot and outdoor event area at the new Toucan, and along with that comes a little bit—quite a lot, actually—of stormwater managment (this inlet, in the photograph above, was covered up a while ago, but there’s something about our name being markered onto “Inlet-A” such that it will end up at the right project that is satisfying—and there are two more inlets, B and C, as well, on our site).

The new Toucan has an “open studio” concept whereby the frame shop, starting to come together, above, will be out in the open, behind the front counter, rather than hidden in the back.

If you remember, the building was an auto shop previous to our acquisition. That refrigerator that has “Magic City Motors” on it, in the photo above, is where the front door is, and to the right of that is one of what were two boarded-up windows in the concrete block wall.

Needless to say, we’ve made some improvements. This will be the entrance on the 10th Avenue side, in the photo above. Our main entrance (where there used to be a garage door) will be off the parking lot, which will be accessible from 2nd Avenue North, and can be seen in the photo below, along with our main art wall, ceiling, and all new lighting.

So…the process of making a new Toucan continues. And we will be open again as soon as we can…. (Subscribing to this newsletter is a good way to stay informed.)

What’s a Cattle Drive Got To Do With It?

I had a professor in architecture school who professed much in the context of the French philosopher, Jean Baudrillard. Baudrillard, who died in 2007, believed that we live in an age of simulation. Reducing his ideas to a laughable oversimplification, but one that will do, we live in a time when it is hard to distinguish between the representation of reality and reality itself. Everything, in other words, is a simulation.

The area to where Toucan is moving, the East Billings Urban Renewal District, recently contained within its boundaries a cattle drive, facilitated and in association with the Northern International Livestock Exposition. Allison and I were there on that Saturday a few weeks ago, breathing in the ambiance of Toucan's new neighborhood, pungent with possibility, and enjoying the industrial/agricultural mise-en-scène.

As a procession of horses and wagons and cows and cowboys and cowgirls and rodeo queens flowed past us, it occurred to me that, in the spirit of Baudrillard, this wasn't a real cattle drive (sorry, sometimes that's just what my mind does). I mean, it was real in that it existed right there in front of us, but it was simulating a real cattle drive, i.e., one that moves cattle from here to there with economically productive means as a process essential to one's livelihood. This was a cattle drive with real cattle and real horses and real covered wagons and the real people who wrangled everything together, but it was staged as an entertainment, and as an advertisement of sorts, to be enjoyed by an audience but also, by psychological transfer, for that audience to associate it with an enterprise district in Billings in a positive way, namely via the romance of Montana farm and ranch culture. If the Marlboro Man had been among them, I might even have hankered for a cigarette.

This klieg light on the simultaneously real and romantic illuminated in my memory a more epic version of a similar event mounted in 1989 on the occasion of the centennial anniversary of the State of Montana's founding. Similar only in its being a "cattle drive," it bore little resemblance in terms of scale. It was called The Great Montana Centennial Cattle Drive, and it was ambitious beyond reason and fraught because of it. It coursed some 60 miles, all the way from Roundup to Billings, and included in its procession thousands of horses and cows, hundreds of covered wagons, and the thousands of cowfolk required to make the whole thing work. It was a notion that blossomed into a spectacle, a simulation on steroids, but it was grounded in a history so baked into the arid reality of the high plains that it almost seemed reasonable.

When this cattle drive clip-clopped into Billings and down Main Street, past the fairgrounds but a few blocks from where Allison and I had recently witnessed its contemporary incarnation, it was reported that 30,000 people assembled to bear witness. I was one of that number, home from college that summer, and made some pictures (above and below this paragraph) on the transparency film(!) that had become standard in my nascent photography practice, something of an architecture school side hustle before anyone was really talking about "side hustles."

This Centennial Cattle Drive spawned something of an industry in commercial, participatory, simulated cattle drives and wagon trains for tourists that continued for many years after (and still does today, at a certain level, but for a while back then, I'm telling you, it seemed like there were horses and wagons everywhere). By that time, in the mid-1990s, I had given in to my vocational angst and left the profession of architecture to better align with what had emerged as my true concern: the artful organization of words and pictures rather than the designed manipulation of the form and space of the built environment.

I'd hung a shingle so as to offer my services and was writing and photographing and filming and designing and directing in that way a creative person in the isolated West must do a little bit of everything in order to sustain any kind of financially-viable existence. The work I did as Imagimark! Productions would adapt in scope and particularity to client or employer needs, from the auteur-like creation of bespoke communications entirely of my own conception to working as an individual cog in larger and more complex creative and production endeavors.

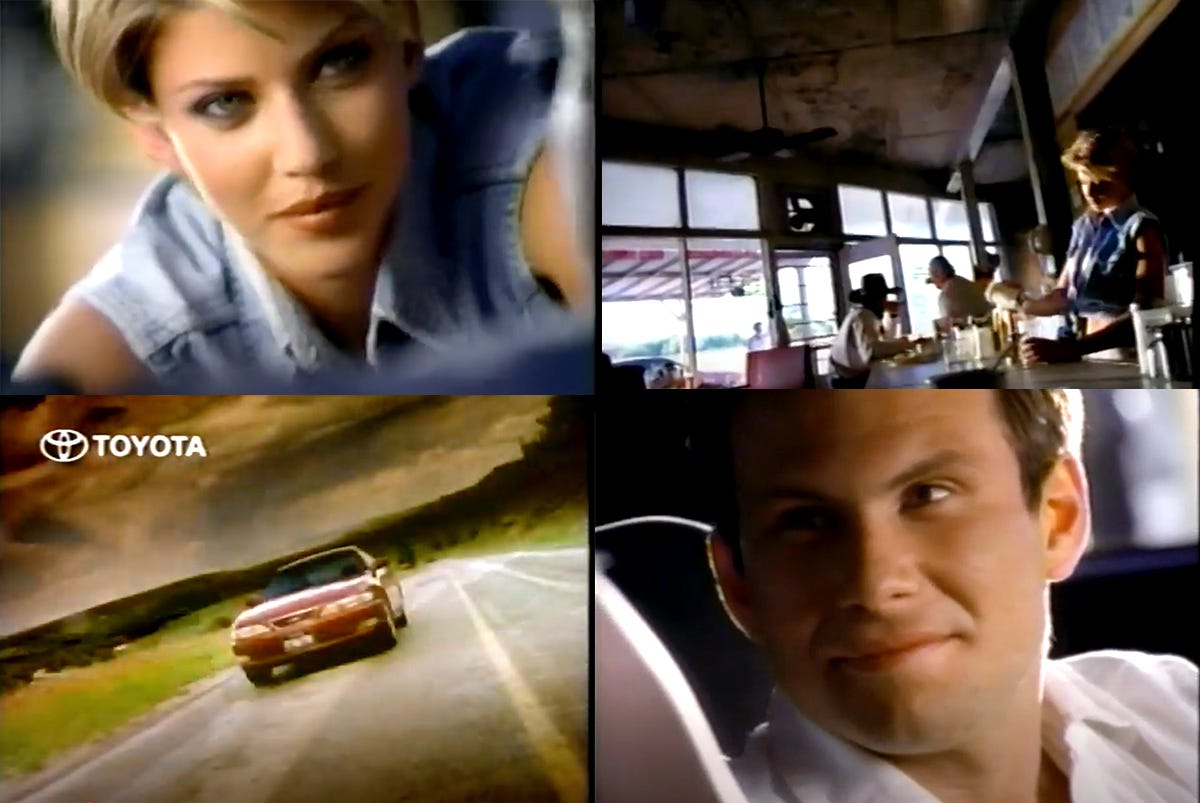

And so it was that in 1995, I found myself providing production assistance for a car commercial in Fromberg, Montana. The car was the newest version of the Toyota Carina, and the commercial would air in the market where it would be sold: Japan. This was a big production, and on set were people from the Japanese ad agency that had conceived the commercial, Toyota's US ad agency, the production company from Hollywood that was making the commercial, a separate crew shooting behind-the-scenes footage for some kind of promotional video (a promotion for the promotion), people from Toyota, someone from the Montana Film Office.

I was working for the production company, a legit Hollywood outfit called Propaganda Films, co-founded in 1986 by director David Fincher. Propaganda was known for its music video and commercial production and brought the talent and high aesthetic of feature films to all its work. Fincher, of course, broke out with films like Se7en and Fight Club and has gone on to make some of Hollywood's most lauded movies: Zodiac, The Social Network, and Gone Girl, among others.

Propaganda had brought a whole crew from Los Angeles. The car had been shipped—on a ship—from Japan to California and then trucked to Montana for the sole purpose of making a commercial in Montana. We were told that at the time, there were only a very few of these cars that even existed, as production was not yet fully ramped up in Japan.

I remember asking one of the producers on the set in Fromberg about this extraordinary effort to make a commercial in Montana that would only ever air in Japan. "Apparently, people in Japan like Montana," he told me.

The production designer had transformed an abandoned cafe in Fromberg, with furniture and gas pumps and other set dressing built and acquired in Hollywood, into a neo-nostalgic setting for the cinematic drama that would unfold in 30- and 60-second versions of this commercial.

Propaganda had hired Antoine Fuqua to direct, an up-and-coming Hollywood director at the time, who had directed music videos for the likes of Prince and Stevie Wonder, and has gone on to direct iconic feature films, including Training Day for which Denzel Washington won the Academy Award for Best Actor.

During production, I would steal a glance at the video monitors to marvel at the mediated version of the Montana reality all around me—a simulated Montana—in Fuqua's exquisite compositions ready to be rendered on film (this was the 90s, big productions like this were all still shot on film), saturated and lush with the Western sun.

Because that's what this was, a little story of a cool guy driving a cool car, a Toyota Carina ED, in the American West, a place like Montana, who pulls up to a cafe and makes a connection with a woman working there. "Who are you?" she asks. This thing was pure Hollywood. A music video mashed up with a feature film, with talent and a budget that left nothing to spare.

The cool guy was played by Christian Slater, and when I asked the producer on set in Fromberg how they'd come to cast him, he told me: "Apparently, people in Japan like Christian Slater."

Slater, of course, had turned heads in his role in Heathers with Winona Ryder in 1988 and had quickly secured his place as both a bona fide Generation X star and a Hollywood bad boy after that. His reputation was still intact on both fronts when I encountered him on set, his mercurial charisma on full display. It was easy to see how his very essence could be readily translated to the medium of film, a supercharged simulation of a human being. When I would see him raise an eyebrow in Fuqua's framing, it was easy to understand why he was Christian Slater and I was, well, me.

The last day of shooting consisted of all driving shots. Slater had left to return to the set of Broken Arrow (this commercial production had taken advantage of the apparent twin loves of the Japanese people and the coincidental convergence of Christian Slater being in Montana making a movie with John Travolta and director John Woo). The other actors had headed back to Hollywood. A professional precision driver was going to drive the car that day, racing back and forth on the road between Luther and Roscoe with a camera—mounted on a camera crane mounted on a camera truck—floating just a few feet in front of it.

We had left early from Rock Creek Resort, where everyone was staying for the duration of the shoot, to get out to basecamp near Luther. I had the Executive Producer, the Director of Photography, and the Gaffer (the head lighting technician) in my SUV. As I drove, the Executive Producer regaled us with stories of the Candlebox video he'd just been working on in Seattle. This was only when he wasn't on his phone, talking to someone in Los Angeles about his next project. Cresting a hill, there was a flash of wood and cloth and fur and I hit the brakes hard and everyone braced themselves and then there we were: bringing up the rear of a wagon train. Expletives had accompanied our rapid deacceleration to horse speed, and as we took our place among the horses and covered wagons in the middle of the road going the same direction we were, the Executive Producer, riding shotgun, immediately began to narrate to whoever he was talking to in LA.

"You won't believe this. I'm in a wagon train. Yes. I'm in Montana and I'm in a real wagon train. No. Right now. It's not part of the job. It's a real wagon train."

And then I'm trying to tell all these hotshot Hollywood guys who have never been to Montana that, well, no, it's not a real wagon train. I mean, it's real in that it exists, and those are probably, like, real cowboys, but, no, this is a tourist thing. Those are tourists in those wagons. It's like, I don't know, a wagon-train business. For tourists.

The Executive Producer continued to tell whoever was on the other end of the line that he was in a real wagon train in Montana because, you know, Montana, and I'm trying to ensure everybody that we don't still have wagon trains in Montana, even though there's one right in front of us, and finally we got to basecamp and everybody moved on to the task at hand, now with the express goal of not plowing into any wagon trains with one of the only Toyota Carina EDs in existence.

This wagon train on the road to Luther, the cattle drive in 1989 from Roundup to Billings, a cattle drive in the East Billings Urban Renewal District a few weeks ago, and certainly a 30-second mini-movie of a girl swooning for a guy outside a cafe in Montana, well, none of it was real. Not real real. It was all a show. A simulation of the real thing.

In Montana, however, we have a privileged relationship to this idea of simulation. Because simulation infused with ideals and desire is mythmaking, and Montana is pretty much made of myth. To most, it is the only Montana they will ever know because most have never been here. I certainly knew some Hollywood filmmakers who never had. And to them, Montana was a figment of their imagination, and once they were here and in it, for real, they couldn't separate their lonesome longing for the movie-Montana in their minds from, well, Lonesome Dove.

For those of us who are here, however, we don't enjoy the same naivete. Our view isn't as obscured by the veil of so many stories, so many screens, so many representations, so many simulations. If the recent "cattle drive" in Toucan's new neighborhood was a cattle drive about cattle drives, mounted for the entertainment of the people of Billings, its artistry was much closer to authentic, the simulation closer to the real, than what I had ever helped Hollywood to do. The cattle drive in the East Billings Urban Renewal District collapsed the distance between myth and reality to reveal a place that seemed that day, if nothing else, true. This is Toucan's new neighborhood, we thought, with the lingering aroma of agriculture and industry in the air, and we’re glad to be here.

In the end, though, whatever the simulation, or dare I say, art, might be—manufactured movie or staged cattle drive among them—it will be myth in its final resting place, in the future, when none of us can any longer speak for it. So I will leave the last word to someone who isn't real (and isn't Robert Duvall), the lazy and loquacious, Gus McCrae, protagonist in Larry McMurtry's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel (and the subsequent miniseries), Lonesome Dove: "The earth is mostly just a boneyard. But pretty in the sunlight."

A Wall of Art

Since Toucan most definitely exists in some kind of unreal suspended animation at the moment, please enjoy this wall of art in Allison’s and my home as a virtual substitution.

Artists represented here include: Rebecca Lee, Kelsey McDonnell, Pat Ritter, Samantha French, Beth Lamphier, Laurie Dewar, Jodi Lightner, Jeff Sandridge, Jason Jam, Thomas Moberg, and Renee Hartig, among others.

These are artists we show, have shown, and have never shown at Toucan. A real mixed bag, ecclectic but intentional. It’s a lot like Toucan at our house, actually.

And Finally…

Could we be anymore excited to share the new Toucan with all of our customers, clients, colleagues, collaborators, and, well, friends. We could not.

Stay tuned. We’ll get there.

Very interesting read! I commiserate with you both, having been through 2 major house remodels, the current one still in process. I send positivity, patience and peace of mind in abundance, as well as the thought that perhaps the timing of all this is perfect (!!!) for reasons as yet unknown. My memory of the great cattle drive of 1989 is witnessing a man have a heart attack, then taking turns doing CPR.... I guess that's as real as it gets. (He didn't survive). In our 31 years living in Montana, we always felt lucky to actually see real cowboys at work, a rare sight. Once, on a drive out in God's country, we crested a hill to witness a cowboy wielding a bull whip in the middle of the road. A bull was on the loose, and as we watched from the safety of our car, he and his compañeros successfully got the bull back under control....A slice of the "real" wild west! I commend you both for your courage, perseverance, vision, and I wish you great success! The new gallery probably won't be exactly as you planned, but very likely better! I wish you many happy surprises and brilliant insights in the coming weeks.

Best of all good things,

Diane Harris