Controlling the Chaos: The Art of Monica Bergquist

A profile of the artist. And a show at Toucan.

Controlling the Chaos: The Art of Monica Bergquist

July 12 - August 12 at Toucan

Opening Reception | Saturday, July 12 | 1 pm - 3 pm

1002 2nd Ave N | 10:30 am - 5 pm Tuesday- Friday | 10:30 am - 4 pm Saturday

Welcome to the Toucan Newsletter!

The format here has evolved a little over the years. This started as a strictly promotional vehicle, a way to communicate what we have going on at Toucan, our art gallery, gift boutique, custom frame shop, and photo studio, in Billings, Montana. And while this will still be the best place to find that information, this publication has become something more of a publication unto itself, so I’m going to organize it a little differently. It now contains a longform essay or article with respect to art, artists, design, beauty, the human condition, the creative spirit, and community, sometimes directly related to something going on at Toucan, other times not and more generally. The “advertising” that supports this newsletter will consist of the promotion of the things that are happening at Toucan. It’s just a little different demarcation with respect to how this thing is laid out, and how I’d like to think about it.

If you are only interested in what’s happening at Toucan, read the little “ads.” If you just want to read something about art and artists and all those other things, read the essay. If you want both, read both. Skim it, scan it, read it, but please enjoy, no matter what.

On with the show.

The artist, Monica Bergquist, laughs. She’s good at this, open to the irony in her own life in a way that allows her to laugh not only at her world, but herself. “I mean, in theory, we really could use this as a bedroom.” She’s talking about her art studio, the room we’re sitting in right now. “But I knew if I took it first,” she laughs again, recalling the work in which she and her husband were engaged to remodel an existing house in Helena, Montana, to turn it more fully into their home, and how she had negated a logical necessity—considering their three school-aged children—to claim the territory as her own. “Maybe we could put a sink in this room,” Monica had speculated early in the process, as if planting a flag.

While this might seem neglectful in the abstract, rest assured that it is nothing such for this dedicated mom, but art has a way of ingratiating itself into certain people’s lives, those without the psychological immune system to resist its allure, its necessity, its torment.

The canvases that surround us are large, the paintings they ground abstract, fluid in their realization, their technique (layering, pouring, mixing, scraping, tilting, so much more), contained only by their edges, the compositions themselves seeming as if they could extend to the boundaries of a state the size of Montana if you let them. Looking at them, hearing about Monica’s life thus far, I try to make a connection, something about her life as it relates to managing her family, a husband, yes, but three kids, ages 6 to 12, and everything they need and have to do. “I mean, I don’t want to call your life chaos,” I say. This comparison is clumsy, but Monica extends the tip of a slim index finger to the tip of her nose, on the nose, and articulates it succinctly, with respect to her artmaking: “It’s a way to control the chaos.”

The artmaking in which Monica is engaged—a sort of chaos in action, a deterministic process that leads to complex organic patterns—could be likened to the drip painting of Jackson Pollock, the iconic Abstract Expressionist of the 20th century, only in a same…but very different…kind of way. Pollack’s flicks and drips and pouring and splashing, some called it action painting, for the kinetic nature of the artist’s application of paint, are replaced in Monica’s work by a manner more controlled in appearance, if no less unpredictable in essence.

She says she finds the process of making her art exhilarating. And on second thought, as our conversation coalesces in that way that you can’t possibly predict from the outset, she realizes and then clarifies that she is not seeking control, necessarily. If she wanted control, she would use brushes and put the paint exactly where she wants it, she explains. This is, in fact, what led her to work in pure abstraction in the first place. She didn’t always paint this way, but, as she says, “If you have a brush and you set out to paint X, it’s almost easy.” If you know where you’re going, in other words, it’s easy to know when you get there. How she paints now is, instead, an adventure into the unknown. The end reveals itself without any preconception, because that’s how a life unfolds. Maybe this means she’s learned to live with a certain level of chaos, to normalize it. In any case, she says, “When I was returning to art, I think it was more that I needed some sort of therapeutic thing.”

Because this story doesn’t start here, in this studio in this house in Helena. It probably starts when Monica was a child, drawing and painting as children do, except the opportunity to make art beyond that moment is anything but a given, which is why someone like Monica must seek it out, and so maybe the beginning, because beginnings are important, was to be found in, of all places…well, as she says, “We moved to Billings when I was 16.”

This move was temporary, as others had been in her young life. Born in Pierre, South Dakota, her parents were co-pastors (as Monica explains, “they were ELCA [which is Evangelical Lutheran Church in America], so Lutheran, but like the liberal Lutherans”—hyphenated names, her mother one of the first woman Lutheran pastors in the 1970s, feminist, that sort of thing) and often moved from church to church. And while Monica left the world of the church behind when she left for college, while she was in Billings, she was still engaged in its traditions. And so it was that at a Billings church, she met a church organist who told her, upon hearing of her artistic inclination, that her daughter was an artist, and so Monica ended up studying with the well-known Montana/Wyoming artist, Arin Waddell, for a year. And at West High, her art teacher let her set up her own personal art space in what was essentially a closet across from the art room proper, the recognition of talent by a perceptive art teacher some kind of gateway to, or permission for, the pursuit of this thing that society neither requires nor expects of you.

It should probably be mentioned that Allison, my wife and partner in Toucan, and I didn’t know any of this until a few months ago, as we didn’t know Monica at all, not until an email showed up in the overcrowded inbox, and Allison said at some point, “you might want to look at these,” and I, after talking to Monica on the phone for the first time said, “she certainly sounds like somebody we would like,” and, well, here we are. But that Allison, when she was a teenager at West High, was afforded that very same personal art space across the hall from the art room by her art teacher (Sara Mast, who now teaches at Montana State University), and that when I was teenager at West High, I would include among a very small coterie of friends, Arin Waddell, this is the kind of connective tissue that somehow makes a person think…well, larger thoughts (which aren’t for today).

Controlling the Chaos: The Art of Monica Bergquist

July 12 - August 12 at Toucan

Opening Reception | Saturday, July 12 | 1 pm - 3 pm

1002 2nd Ave N | 10:30 am - 5 pm Tuesday- Friday | 10:30 am - 4 pm Saturday

Anyway, it was during these couple of years in Billings, with these influences and frequent trips to the Yellowstone Art Museum, that Monica realized that she did indeed love art. So off she went to art school at the University of Montana. And everything was going well. This is the path for many an artist, of course. Her parents were supportive. Society approved of a college education. She did a year in Hawaii, one of those exchange kind-of-deals, which was amazing she affirms. “Their art building was open air, so you were doing a lot of things mostly outside.” (By which she means: outside in Hawaii!) But when she came back to Montana, something was different, the tenuousness of her whole endeavor to make art, to be an artist, in the context of the real world, so to speak, well, it was exposed in a way that made it all just a little too uncomfortable. It could be that making art in Hawaii is just too much of a good thing, a fantasy, even if you know you lived it because you actually lived it. Because while her parents were supportive, their voice was not silent. “What job are you going to get? Like, what’s going to be your career?”

Every artist’s life is a question, an answer in the end, but a question as it unfolds, a question as to how an artist is supposed to exist in the world. Or as Monica puts it: “When I got back, it was, okay, gotta get serious. So, I switched all the way to science.” And there it was. It had happened again. That ‘A’ so tenuously lodged between the ‘STE’ and the ‘M.’ Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math. With the ever so fragile ‘A’ for “Art” dislodged and broken into so many pieces, STEAM the lesser water (not by any means a river, don’t get me started on ice) blowing away in the wind, the course of things corrected in our time, for our time.

In Monica’s case, this wasn’t cynical or grim, though. This was earnest and true, much more than some kind of defeat. She was a health nut, she admits. She had always liked science and math, and was obviously able to do it, because an undergraduate degree in art led easily, if incongruously on the surface, to a graduate degree in the nutrition sciences, and the next thing you know, Monica Bergquist was a registered dietician.

She was a registered dietician who could draw and paint, but her patients didn’t care so much about that, probably didn’t know anything about it, really, since she had so thoroughly left it behind. She was on the east coast now, working in clinical settings, hospitals. She had been for a while, when she began to feel like maybe something wasn’t quite right. It could have been when she was covering for a maternity leave in a 30-bed, high-level trauma, neonatal intensive care unit, when she realized that, you know what, “I don’t like this.” Which in the end was the end. She just couldn’t do it anymore. Those babies. A lot of them don’t make it. The parents. Hospitals, in general. All of it.

She moved into research for a while, which she really liked, she says, but even that couldn’t satiate a certain thirst, so after ten years of it, these real jobs, this career, she went to work at a bakery in New York. This wasn’t a cop-out or even a refuge. It turned out to be a lifeline. A way to get back to the shore from which she had departed. She could feel it happening. A transition. Baking was making. She was creating again.

But the path back to art isn’t any easier than the path toward it in the first place, even with a lifeline, because art is only a part of life, and as Sartre wrote, “everything has been figured out, except how to live.” Monica’s father was in a catastrophic bicycle accident and her mother was diagnosed with cancer. These are the complications that do more than color a life, they throw the whole thing off its axis, a meteor crashing into the planet of your existence. Monica was pregnant with her third child at her mother’s funeral.

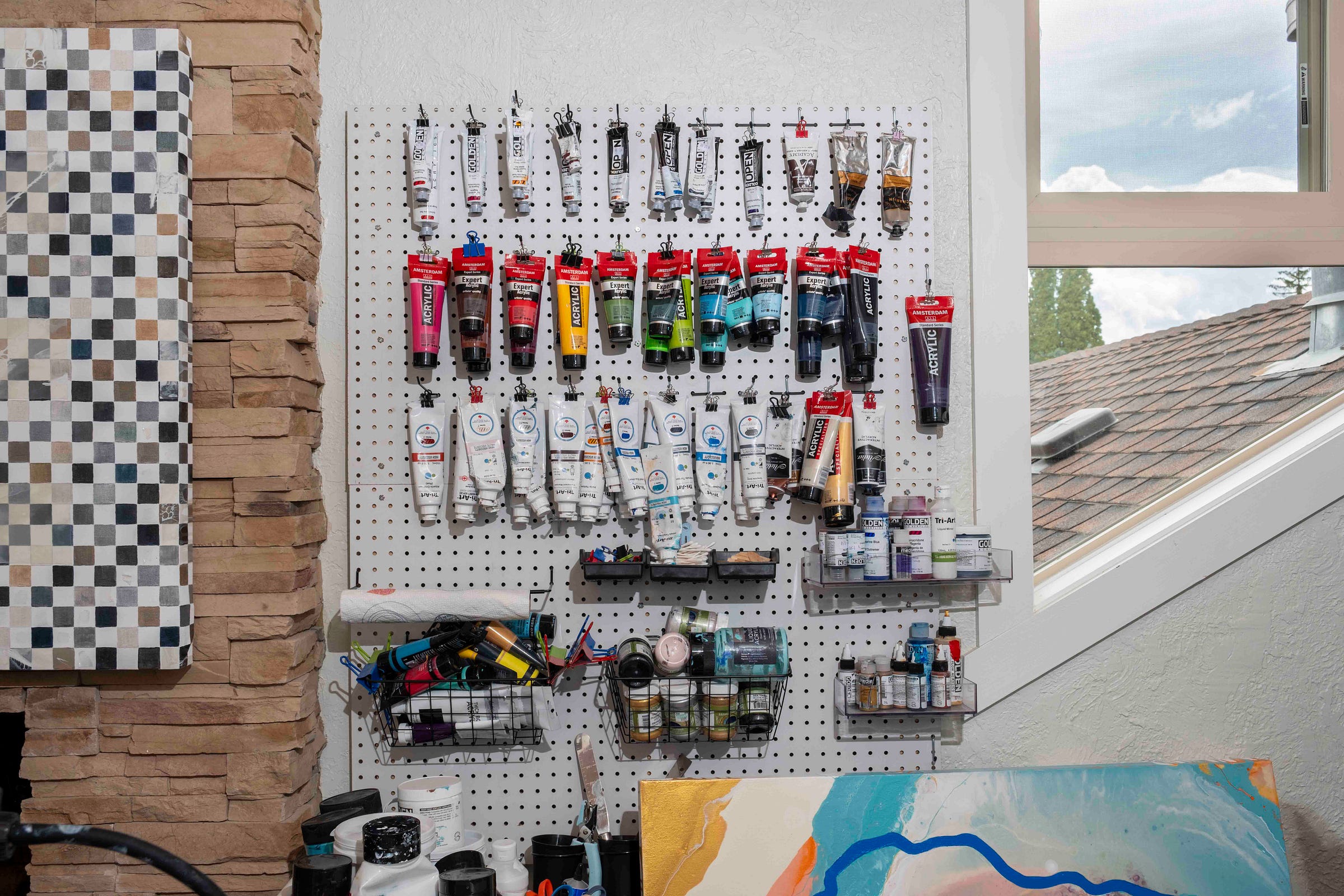

The consequences of life are tallied as we take them, for some a magnitude greater, their bloom earlier, but whatever the proportion, the artist has something that a layperson, shall we say, does not, which is something to do. Making art can be an escape valve for all the above. The lifeline, it finally led Monica and her husband and kids back to Montana and today, sitting here in her studio in Helena, surrounded by these large canvases, works in progress, a consequential and meticulously organized store of art supplies—that sink—Monica tells me that she finally feels like she is home: “I don’t think I’m going to leave this time.”

Monica’s current artistic pursuit, The Flow Series, will be shown at Toucan from July 12 to August 12, with an opening from 1 to 3 pm on July 12. This series of paintings is profound in its integration of Montana’s ultimate organizer and signifier: rivers. It’s an addition to these complex depictions that provides a psychological foothold and a meaning unique and affecting to us here in Montana (she’s even using the water from each of the rivers depicted to mix her paints…yet another layer). These paintings represent the chaotic and unknown contained, whether between borders or within self. Our rivers themselves barely controlled by us, a power greater than we. The geometry against the unknown, the spirituality of it all. This is Monica’s testament to a life lived, still being lived, and that will be lived.

There is a theory about chaos, chaos theory it’s called, and it concerns itself with complex systems and the idea that their behavior is highly sensitive to initial conditions, to beginnings. This sensitivity, which is often called the butterfly effect, means that small differences in starting points can lead to vastly different outcomes over time, making long-term prediction extremely difficult, even though the system follows natural laws or rules.

Which is to say, a butterfly flaps its wings. A girl is born in South Dakota. Monica Bergquist is a woman of unpretentious grace, warm, vital, with a smile that seems like it comes from contentment but could just as easily be the baring of teeth against an unruly world. Either way, it’s probably best to realize that if she is working with and through the chaos of the endeavor to be human in her work, maybe her work is ultimately a reminder that so can we.

Controlling the Chaos: The Art of Monica Bergquist

July 12 - August 12 at Toucan

Opening Reception | Saturday, July 12 | 1 pm - 3 pm

1002 2nd Ave N | 10:30 am - 5 pm Tuesday- Friday | 10:30 am - 4 pm Saturday