Toucan, BIRD(S), and the Exquisite Corpse

The end of the process of making a new Toucan, and the beginning of so much more...

Hello!

As you know, we’re up and running in our new location, a refreshed and reinvigorated Toucan in Billings, Montana for what? A new era? The next big thing? A sublime and noble future? (Is that possible?) Whatever it might be, we made a place for beauty and creativity and light and hope in our little northern industrial town.

Since I don’t have to update on construction anymore (although work is just now resuming on our landscaping, which had to pause for winter, such as it was), this, the newsletter version of Toucan, can move onto other things.

First up, let’s put on a show!

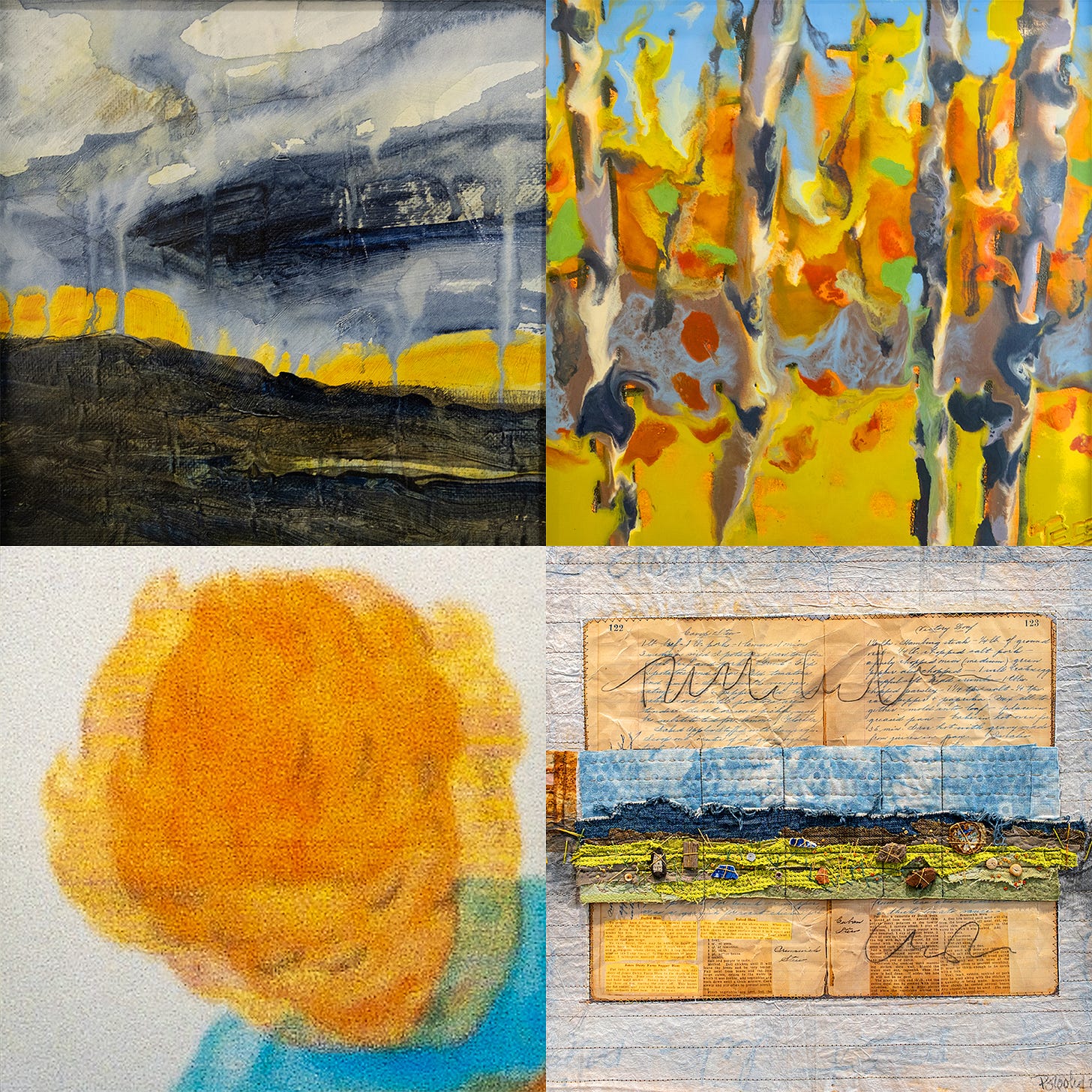

We’re inviting artists, designers, architects, and builders of all kinds to participate in an invitational show at Toucan.

It’s a callback to a fundraiser that Toucan was involved with in 1996 that had artists and craftspeople making birdhouses. This new iteration is meant to recapture that spirit and highlight the contemporary creativity in our community in a multidisciplinary way by including artwork and design of all kinds, including fine art, constructed birdhouses, and conceptual birdhouses.

The theme of “bird,” singular and plural, is certainly a play on the various ways in which Toucan finds itself associated with it, i.e., a toucan is a bird, Toucan is in the BIRD (Billings Industrial Revitalization District), we like birds, etc. We look forward to a wide variety of interpretations.

There will be a show and sale to coincide with a Grand Opening Celebration in June.

All the information (and an entry form) is here: birds.toucanarts.com

Process and the Exquisite Corpse

From the Age of Enlightenment onward, people have worshipped the artist as a secular god among humans, someone to revere as a seer—a see-er—greater than oneself. While historically accurate, however, this is realistically absurd. Artists aren’t gods with otherworldly abilities. They have neither divine talent nor supernatural genius. This elevation beyond the bonds of earth is understandable, though. Forgivable. We desperately want things to distract us from the mundanity of the relentless progression of our every days. The angst wrought from our terrestrial human existence is thus mollified by the products of the artist’s process. Art is our savior, even if its making is not heavenly but rather hard work.

And while the gift of a fortuitous shuffle of the genetic deck cannot be dismissed in any estimation of talent—otherworldly in its mind-bound mystery—it is ultimately in the dedicated practice of making art that whatever the genius of the artist is realized. Over and over and over and over and over and over again the artist is dedicated to making art in a way that normal people are not. And while this dedication to the practice is the earned capital of the artist in the marketplace of human endeavor, the process of making art, the process of making anything, well, it’s free and unbound, accessible to all.

Process in and of itself first emerged in my field of vision, academic and analytical, when a book, The Universal Traveler by Don Koberg and Jim Bagnall, showed up on a reading list for a first-year design studio when I was in architecture school. This book, while on the syllabus, was never actually assigned. I asked the professor about it one day, to which he replied: oh, yeah, that’s a pretty good book. And while he had apparently not reviewed his own syllabus recently, and the offhand nature of his pedagogy seemed suspect at the time, this slim volume completely, fundamentally, changed my understanding of design and the process of creating, well, anything. In fact, all these years later, I view the resultant M.Arch as a degree in process as much it ever was something to do with architecture proper. (And as a result, I’ve been able to use it as the foundation for my work, my practice, across the variety of creative disciplines that have made up my career.)

In our recent reinvigoration of this thing we call Toucan—in brand, mission, and mostly place—process, then, was essential, at the same time that it was, essentially, benign. Because the thing to know about process, in general, and the creative process, in particular, is that it is empty, devoid of content. It’s merely a series of discrete stages that make up a system for thinking. In the case of the creative process, it’s a system for, yes, creative thinking, that particular work of the mind that results in products novel, new, never before known or seen.

It is because of its nature, of course, that the creative process is available to everyone, and artists aren’t special. By which I mean, artists are special, of course, it just isn’t special that they know the process of creating things. Anyone can know that. I can teach it to you. What you do with it, however, will ultimately be judged by the field of experts (and, yes, especially in today’s social media miasma, everyone is apparently an expert) who will determine the true merit of the product of your practice. And this is where the artist has the upper hand in making art. They fill the framework with a higher knowledge and talent, whether genetically gifted or diligently practiced. Perhaps the greatest gift of all being a penchant for rigorous practice.

1) Preparation 2) Incubation 3) Insight 4) Evaluation 5) Elaboration. These are the discrete and defined steps of the creative process, a system that can and has been defined and redefined, rethought and refined, continuously since it was first scratched into whatever academic stone. This one just delineated comes from the renowned psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and is generally thought to be definitive. As you can see, however, in order to be effective as analysis, i.e., the (seeming) simplicity wrought from separation into component parts, the whole of creativity remains unreasonably complicated, lost to mystery, the realm of wizards.

This analytic simplification is, however, why the process itself is so easily contained, commoditized, and sold in the marketplace of ideas. In fact, look at this: 1) Frame a Question 2) Gather Inspiration 3) Generate Ideas 4) Make Ideas Tangible 5) Test to Learn 6) Share the Story. These are the steps of a “human-centered approach to innovation” that the global design firm IDEO sells to clients and customers who are ostensibly “inventing the future.” IDEO utilizes this process to do their work on behalf of clients—and this firm has designed a lot of groundbreaking and influential solutions and products over their 40-year history—but they have also packaged and sold this process directly to clients as a discrete product. They branded it “design thinking” and the term has become fashionable in the business world.

This process, then, however its steps are delineated, and whether it be in the context of art or business or whatever, is relatively easy. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. But the result it produces, the product—let’s call every product of this process “art” of some form, whatever it is that is meant to improve the condition of our lives—is the result of the humanity, the human genius, that infuses it. And that’s where it becomes hard to quantify, and the discrete steps of the process become blurred together, especially by a practiced mind, the way two primary colors, blue and yellow say, are squeezed onto a palette, then brushed into a painterly Venn diagram with green as the result of their overlap, but not in a direct 1+1=2 way, because there’s that bit that is green but streaked with a little of the yellow still distinct, or that part you can’t really say whether it’s green now or still really blue, the way the world and life are too complicated to be reduced to easy answers, like Blue or Yellow or Green.

There’s this method of creative production, some have maybe even experienced it as a party game, called “Exquisite Corpse.” The exact date of its genesis is disputed, but it would seem that Surrealists in Paris in 1925, gathering at a home in Montparnasse, and including André Breton, Yves Tanguy, Jacques Prévert, and Marcel Duchamp, passed around a sheet of paper whereby one would write a few words or a phrase, fold the paper to hide what they had written, pass it to the next participant who would follow suit, and so on, eventually to reveal at the end a construction, a sentence, simultaneously contrived and unknown. Apparently, this phrase was produced on that fateful night: le cadavre exquis boira le vin nouveau. The exquisite corpse shall drink the new wine. The game would evolve to include drawings of body parts and exquisite corpses have been produced by artists as famous as Frida Kahlo and Lucienne Bloch.

Which is to say that while a work of art is often thought to be a specific product of direct human intention—coursing along the discrete steps of a defined process—the serendipitous output of calculated randomness that defines the exquisite corpse is perhaps much truer to humanity’s creative urges at whatever the scale.

The process of making art: does it propagate, unfurl, unfold? Does it smoosh, smear, spatter, even? Whatever the case, whether psychological or cybernetic (the branch of systems thinking from which these ideas about creative and/or design process originated), the process doesn’t make The Art, the artist does, and while I began by implying that the artist is not divine, that doesn’t mean to think any less of the open vein, for indeed the artist is the ultimate vessel of manifest genius, however it might bleed, however the process might be run.

The philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, when comparing the poet to the philosopher, wrote that the former presents flowers while the latter their essence. So best to end with the words of a poet, that great poet of Missoula and the Pacific Northwest, Richard Hugo, from his classic collection of lectures and essays, The Triggering Town, “...by now I was old enough to know explanations are usually wrong. We never quite understand and we can’t quite explain.” I choose to accept that as the final word and raise whatever is left of my reflection in the bottom of a whisky glass to toast the future and that our corpses be exquisite when each of our journeys is finally done.

Links

Miscellanea from the internet…

Diller Scofidio + Renfro, architects of the original building, have been commissioned to expand The Broad art museum in Los Angeles, increasing its gallery space by 70%.

The Whitney Biennial, described as “the longest-running survey of contemporary art in the United States” is underway at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York until August 11.

Here’s the era-defining sculptor Richard Serra’s New York Times obituary (this is a gift link for those who don’t subscribe).

With respect and sympathy to Kate Middleton, the Princess of Wales, an interesting take on Artnet points out the fact that she was not the first royal to have their portrait edited.

You might have heard about Beyonce´’s new country album, but you might not know that there was some guerrilla marketing afoot when promotional images and slogans were projected on New York art museum exteriors, including the Guggenheim, without any of the museums’ knowledge or authorization.

Uncle Vanya, one of my favorite Chekhov plays, opened for previews this week at Lincoln Center in New York, with a new translation by playwright Heidi Schreck and Steve Carell in the title role. Playing the overworked and brooding Doctor Astrov, is William Jackson Harper, with the prescient line early in the first act: “One hundred years from now, the people who come after us, for whom our lives are showing the way—will they think of us kindly? Will they remember us with a kind word?”

Books

Here are some of the books referenced herein that might be of interest to some of you. (Also, you might not know that Toucan is an affiliate of Bookshop.org where your purchases support independent, local bookstores, including This House of Books in Billings. Toucan will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase below.)

First off, The Universal Traveler by Don Koberg and Jim Bagnall, published in 1973 is out of print. I’ll just note, for what it’s worth, that the process delineated therein goes like this: 1) Accept 2) Analyze 3) Define 4) Ideate 5) Select 6) Implement 7) Evaluate. Maria Popova has a little bit about this book on her blog, The Marginalian.

The Death of the Artist by William Deresiewicz. This isn’t referenced specifically anywhere above, but is a sharp and probing examination of the state of being an artist in today’s economy, with a particularly clear look at how the place and understanding of the artist has evolved over our human history.

Creativity by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

Change by Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires Innovation by Tim Brown, former CEO and now Executive Chair at IDEO

Essays and Aphorisms by Arthur Schopenhauer

The Triggering Town by Richard Hugo

The Plays of Anton Chekhov by Anton Chekhov

Upcoming

Schedules are coming together, stay tuned for exact dates on some of these things.

May 3 | The recipient of the first Toucan Emerging Artist Award will be announced. This monetary award is given each year to a graduating senior art student at Montana State University Billings. It’s a little seed money to launch their artmaking outside the walls of the academy.

May | The return of In Conversation at Toucan, our series of in-person conversations with artists and other creatives in our area.

Also in May | For what it’s worth, I’ve been summoned for Jury Service by the United States District Court.

May 31 | Deadline for BIRD(S) invitational show.

June | BIRD(S) and Grand Opening

September 5 – 8 | Wild West Walls in the BIRD (there will be murals)

In the End

It just might be best to pour a beverage, orient yourself toward the setting sun, and read a poem. Might I suggest “Degrees of Gray in Philipsburg” by Richard Hugo. It’s on the Poetry Foundation website.

Cheers, everybody! Allison and I look forward to seeing you soon.